3____Transparency

The concept of transparency in art discourse has many nuances. The Aristotelian ideal of the perfect artwork, where different media in a work dissolve through each other to serve the mimetic integrity has been described by Clement Greenberg as “media transparency[1]”, in opposition to his ideal of the perfectly opaque, medium specific art practice. However, transparency in art practice can also refer to the act of revealing the mechanics of the process of creation or performance. It can be used to describe art where traces of the creative process remain in the final work, or where political or economic interest involved in the making of a work are open to the viewer[2].

In theatre it could refer to the practice of Berthold Brecht, where revealing the simulacrum of the mimetic intention is a way of engaging the audience on an intellectual level, a stripping away of artifice. There are also negative connotations to the idea of transparency: In contemporary philosophical discourse, it may refer to the idea of “digital panopticon”, where social media turns our private lives into glass houses, or the way the striving for transparency on a social level or institutional level, can lead to conformity in a way that one set of values or norm are prioritised over others[3].

Earlier in the paper, the idea of hypermediacy was discussed as a form of opaqueness where a score’s mediacy becomes apparent. This is not in contradiction to the idea of transparency that I find fascinating as an attribute of the media score. Here the transparency is created between the score and the audience, where the code used by the musicians is shared with the listener. Whether the information that is shared with the audience is relevant or significant in any way in enhancing the experience of the work might be questionable, yet the possibility of sharing the blueprint of the music gives the audience the opportunity to engage in multiple ways.

The look of a concert can seem odd to some. Music stands create a barrier between the musician and the audience, dividing the listening space. This division goes beyond the architectural separation already present in traditional concert halls. The layer of information in the notation—unseen by the audience—serves as a hidden text that musicians translate into sound. This setup inadvertently reinforces the roles of musician and listener. It is a convention accepted as the norm in classical music performance, largely due to its advantages: top-down organisation, the ability to perform large-scale works that are difficult to memorise, fine control over expressive nuances, and the option for sight-reading. The convention of using music stands persists from a time when music alone was prioritised as the ultimate form of expression. Musicians focus on reading the score, while the audience concentrates on listening, creating a connection through sound in the shared space. But does this model still resonate in an age so dominated by the visual?

Yet not all music performance relies on the use of printed music and stands, this has become a convention in classical music (when the performers are not playing by heart), and certainly in much contemporary classical composition. The reliance on notation during performance (rather than as an aid to transmitting the composition solely during rehearsal period), has something to do with the socio-economic structures of contemporary classical music, how much rehearsal time can be allotted to a concert, and the conventions that have sprung up around it. Learning a piece of music to the level that no music part and stand is necessary, certainly helps to communicate the essence of the score, because the dedication and time spent on learning it is apparent and conveyed by the musicians. I remember hearing the ASKO Ensemble, when I was an undergraduate student at York University in the early 1990’s, playing Edgar Varese’s Octandre, standing with no music parts and no conductor, and being struck by how vital an experience that was. This is a rarity in contemporary classical music, the immediacy of the music seemed to be amplified by the closeness and direct contact the musicians had with the audience.

One way to address the barrier created by music stands is to share the score with the audience. By projecting the score in the space, the division of roles can be softened, allowing the audience to share the musicians’ perspective. For some, these visual symbols might deepen the mystery of music-making; for others, they could make the experience more accessible and engaging. However, this transparency comes with potential drawbacks: not all audience members can read music, and those who can, might focus so intently on the connection between score and sound that their listening experience becomes more analytical than emotional. Additionally, the performers’ presence might be overshadowed by the audience’s attention shifting toward the projected notation.

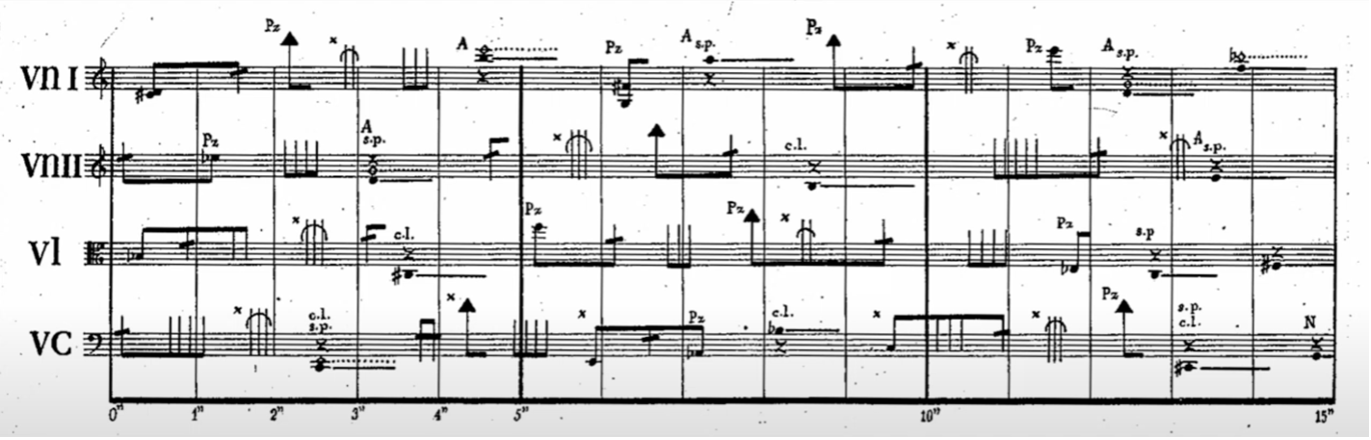

Some successful examples of using projected scores for audiences are those where the graphic elements create a strong visual impact or where the score itself is so distinctive and beautiful that sharing it enhances the audience's understanding of the piece. This is often true for "graphic scores," where the visual elements carry significance beyond instructing the musicians. As mentioned earlier, the immediacy of the score can also offer an intriguing perspective for the spectator, as well as aspects of aboutness and metaphor.

An example of the performance of a work that was never intended to be used as a projection, but because of its peculiar graphical beauty, gives an audience an insight into the workings of notation is the Kronos Quartet’s performance of Krzysztof Penderecki’s Quartetto per archi (1960)[4]. The score is rendered in scrolling form, with colours inverted (black background with white notation), with a red vertical stripe in the middle letting the musicians and audience know what is being sounded at any given moment—a karaoke version. This simple device of animating the score, not only helps the musicians synchronise a relatively arrhythmic musical texture, but also demystifies the music for the audience.

Cat Hope, a composer known for her pioneering use of what she terms “screen-scores,” often employs similar techniques and has written extensively about the development of animated scores, as well as the advantages and disadvantages of projecting them for audiences. Reflecting on her piece In the Cut (2009)—a quintet exploring gradual and continuous pitch descent—Hope discusses the challenges of presenting simplified visual information. While this approach can help avoid overwhelming the audience with overly technical details, it may also oversimplify the way the audience perceives the sonic complexities. She notes,

“They perhaps even experience the sounds differently because they are visualized in this manner[5].”

Additionally, she observes that the dramatic narrative of the music can be affected if the audience is able to anticipate what is coming next.

Both scores cited here utilize the "scrolling" aspect of projected media scores. This approach offers several advantages, such as precise timing—especially in music where meter is not a natural feature—and synchronization for both musicians and the audience (if the score is projected). However, this method comes with trade-offs, as it limits the amount of musical information that can be processed by the audience at any given moment. Providing the audience with the same view as the musicians can be a double-edged sword: it creates transparency but also narrows their perspective, particularly when conventional musical notation is used. The "karaoke-like" relationship created by a highly functional score shared with the audience can be mitigated by incorporating richer visual elements. For example, these elements can expand the audience's perspective or foster a more complex, metaphorical connection to the music.

The “Karaoke-ness” of this approach was my own first exploration of the media score, Karaoke Etudes (2011). Unlike many of my later works, which are interactive and generative, this piece is a fixed-media audiovisual score that engages with the material of karaoke. What initially drew me to the subject was my fascination with the way text is displayed in karaoke—how lyrics are presented. In Karaoke Etudes, an abstracted form of musical notation is developed for musicians to read alongside the text, incorporating familiar graphic tropes of karaoke in a more abstracted form.

The fragmented lyrics are not meant to be sung but rather read by the audience (or sung internally through their "inner voice"). Each movement is designed for a solo instrument, accompanied by an open ensemble. References to famous songs appear within the lyrics and sounds, though they are never explicitly revealed. The score provides ample space for improvisation by the soloist and ensemble. However, because of the text's prominence in the visuals, the audience is not overly focused on the relationship between the score and the performance. Instead, they are invited to experience the media score from a fresh perspective.

There is a sense of transparency here: the musicians and the audience are engaging with the same score, seeing, and hearing the same elements. However, the signs within the score hold different meanings for each group, creating a layered experience where interpretation diverges while still being rooted in a shared framework.

Next: Adaptability

Notes

[1] https://csmt.uchicago.edu/glossary2004/specificity.htm

[2] https://interartive.org/2013/04/instances-of-the-transparent

[3] https://philosophynow.org/issues/158/Seeing_Through_Transparency

[4] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JwUZao6pokM

[5] Hope, Cat. The Aesthetics of the Screen-Score. January 2010. Presented at Createworld 2010, Griffith University, Brisbane.