Introduction to the practice

I organised the portfolio of works (twelve in total) in three containers that cover different ranges of risk when putting parts of my ADHD self in contact with another. What I include as 'works' in the portfolio is an asymmetric spread of artistic manifestations, some are more of a simple sketch or idea encapsulated as a temporary object, others are more complex pieces and others still which are research workshops done in deep artistic explorations with other artists but with no audience.

Organising the works in separate containers helps foreground the different creative strategies I've taken depending on the kind of performative risk I could withhold at the time. I present the works in an approximate chronology which helps expose the evolution of the practice over time.

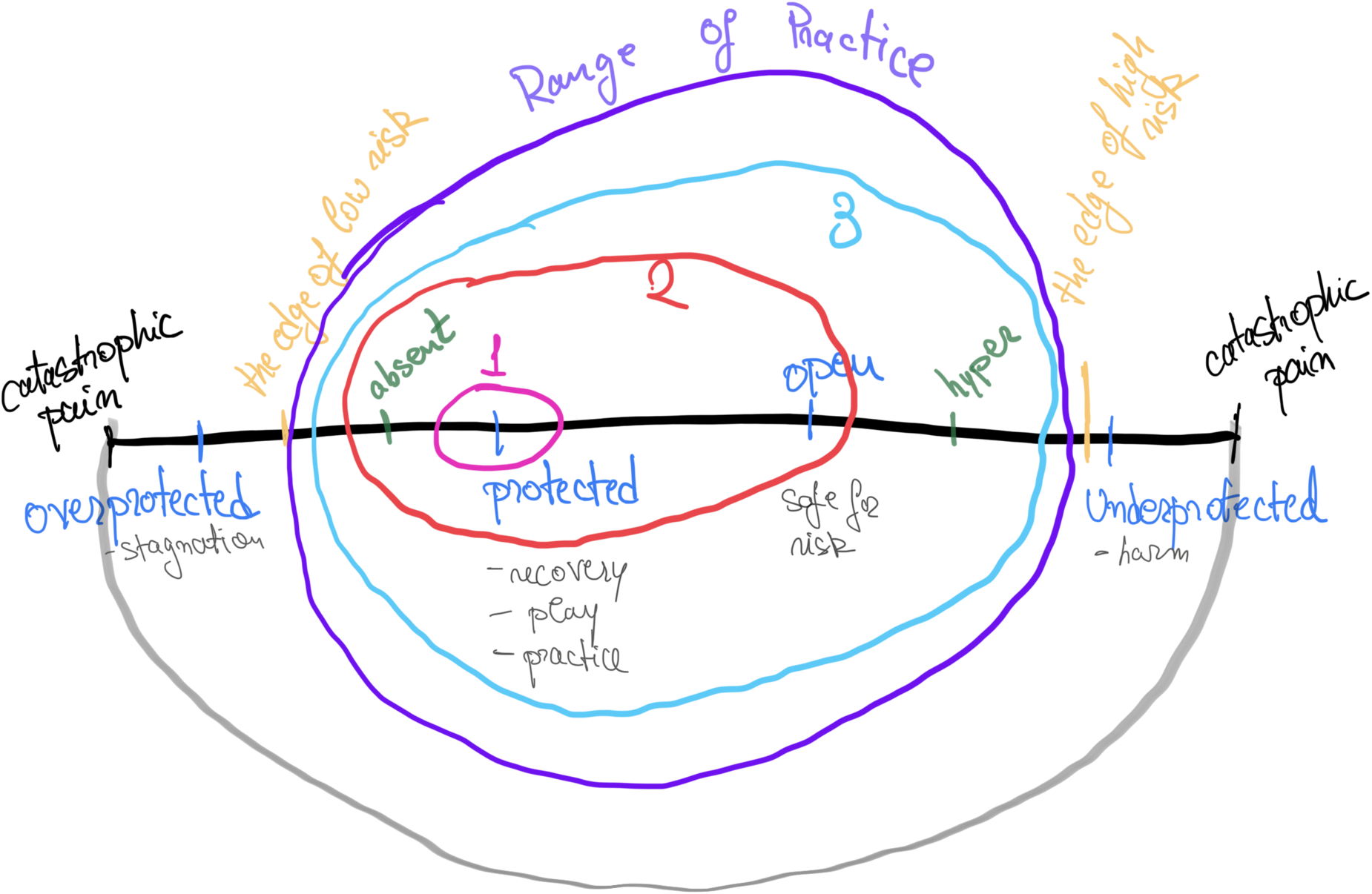

Throughout the development of the practice, the question has been about the kind of risk I am capable of withstanding and what expression I can access by doing so rather than the amount of risk that I am able to withstand. The range of risk I present below opens up the possibility of a qualitative spectrum defined by the different states of selfhood.

The spectrum ranges between:

- an overprotected self - a guarded self in which expression is completely muted, stale, stagnant, impossible to express

- and the underprotected self - a dissipated self that has travelled outwards, has been exploded open by too much intensity, hyperstimulated by external distractions, temporarily lost and unable to return home.

On the big, vast outside of these there is catastrophic pain which is always lurking around as a possibility given that so much of the self is involved in the act of making. This pain can come out of isolation, invisibility, stagnation or out of too much stimulation, relentless action without pause and can be catastrophic in the sense of becoming incredibly difficult or impossible to regain fluidity of movement, to recover and reset, to escape a given condition.

Within the range of risk I flag two more states of selfhood: a protected self and an open self. The protected self might not reach exposure directly, mediating its expression through objects, recordings or other strategies that keep the body in a protected cocoon of sorts. This is expression (particularly female vocal expression) that is easy to consider as weak, insecure, soft, fragile, quiet, muted and dismiss as uninteresting or unimportant. This is expression that might require care and generosity from the listener and a variable proximity so that the protected self can generate and regenerate.

The open self is a self that is in balance - a self that is secure of its location, position and power and can open up to be witnessed without dissipating away. The open self is a self that reaches out, perhaps over a bigger a distance, moving towards the listener without much loss of energy. The open self is a self that is hard to not idealise and fantasise over - it's what I perceive as the mainstream standard of expression and of performative success - a self that offers consistent focus with confidence and certainty over where and how one is.

The containers, represented by the numbers 1,2,3, in the hand scribbled diagram above, follow an approximate chronological progression of the practic. The fact that over time the range of risk the containers occupy extends in both directions in the diagram rather than concentrating around the open self is a particular characteristic of this artistic practice. Instead of asking myself what I can do to be more like the ideal open self, I've allowed my expression to feed of the different needs and abilities I organically possess, staying inquisitive about how it is to create with the protected self as well as the open one and everything else in between.

Over time, what became of creative interest to me is how to be at ease sharing expression that has the possibility to fluctuate freely (erratically or not) between different types of risk, rather than aiming for a balanced middle ground where one risks only in the right, 'ideal' way.

Expressively what this means is that one (myself or another performer I work with) is given permission and supported to be sharing immensely intense sensations through sound while in the next breath (or later) retreating inwards to recover, calling forwards a performativity that looks like an unfocused or absent self, an automatic sound or a sound that doesn't leave the body, to recoup or recover from the initial effort. In this kind of expression, the body of the performer courts extreme risk, tending towards it, playing with the possibility of destruction and the excitement that the high stakes bring.

From an ADHD perspective, this type of extreme risk brings with it a stimulation that motivates, that gives purpose and meaning to expressive action, tempting and testing what might be easily acceptable, being intentionally provocative. Because there is risk in either direction of the underprotected-overprotected scale, ultimately the goal is to find a balance by fluctuating over this higher expressive range, moving freely between different types of risk. From a sonic and performative perspective, sound has both form and function: its function is to put my body into direct connection with its own desires, following and materialising impulse, leaning into what the ADHD body has to offer, enabling and supporting this neurodivergent expression. As a consequence, its form or material carries visceral sensitivities that vibrate, spill or erupt out of the body, sounds that closely follow biorhythms, sounds of embodied processes.

The first container, 1. ‘At a distance from you’, covers three works that focus on self-sensing. The processes of development as well as of witnessing the artworks are done without any one making contact with my body directly. I connect with others via pre-recorded versions of my voice or through someone else's body (when working with musicians).

In Drawing 10 red+black (2020,2024) I’m using recorded voice, a voice that can only manifest itself in isolation, unobserved by others directly.

In Ecstasies of Rooms (2020) - with Christine Cornwell, I encourage other bodies to follow a particular kind of vocal activation through an audio score.

In sound mattering study: Elisabeth in the Hague (2021) - with Elisabeth Lusche, I work with a musician to develop and refine a method of embodied work that transfers from voice to trumpet.

In these instances, the artistic intuition and knowledge have been acquired through my body, but I am not risking the encounter with another directly.

The second container, ‘Risking encounter, designing the context’ focuses on participation and the design of performative contexts that can hold and support my body to connect with others under specific circumstances. The three examples I present here build on one another as I learn more things about what my body and voice can do and what kind of experience I can hold and withhold in participatory performance settings. In the type of participation I offer here there are no right or wrong ways for a participant to engage in the performative setting and no agenda of what is expected to happen. Despite of this, in some works there is a repeatable performative arc or permeable framework that could be disrupted. I discuss the specifics of this participation in more depth within this section. The three examples are as follows:

Balancing Art Residency(2021) -with Julita Hanlon and Chonghe Fan, is a durational performance in an art gallery within a physical sculpture co-created to offer stimulation and potential places to hide/retreat to.

Tea Break (2022) is a one-to-one tea making experience in which I blend tea, inviting the sensory activation from herbs and warm, relaxing liquid to enable a close bodily encounter with another. I use voice to share the common momentary knowledge formed between two strangers.

Ecstasies of Things (2022)- with Christine Cornwell, takes a step forward from Tea Break - working with objects, voice and 4 public participants in a sensory incoherent and playful seance. Voice as an opener for a sonically informed tactility.

In the third container, ‘With others, with help’, my body is present, and I am co-creating performances with others. I focus here on the importance of building trust and safety between collaborators and what effect that has on expression.

In the first work, the creative duo Sun Infusion,collaboration with my husband, artist Tim Murray-Browne, thrusts me into a semi-structured improvisation in front of a typical gig audience for the first time in ten years.

A softer sound, an earthquake (2022)with Feronia Wennborg, looks at a collaborative relationship built over time that resulted in a stripped-down vocal-violin duo in a black-box performance space. The sensitivity is very zoomed in, intimate and personal to our collaborative encounter and to the context.

Experimental Karaoke Juice Machine (ExKaJuMa) (2023) is a live-streamed performance in which I improvise live over ten audio tracks send by a different collaborator. This was an experiment designed to tap into my embodied sonic powers as I attune to sounds made by others without any other bodies present but mine. It was an over-threshold performance that showed what I do not have capacity to do in a sustainable way and confirmed the importance of body-to-body connection.

The Splendor micro-residency (2022) in Amsterdam offered a focused space for me to lead workshops using physical and sonic exercises that I borrowed from more established practices (Roy Hart, Action Theatre), testing what kind of embodiment opens up routes into the erratic and erotic world for others to inhabit.

After a 9-month visiting researcher position at Concordia University in Canada I pre-selected specific performers and hosted an Embodied Improvisation Research Workshop (2023).This kind of practice questions the possibilities of emergent co-leadership and explores more specific somatic approaches to sonic based expression.

I then interrupt the audio-visual way of presenting the practice with a written up break down of my Sonic Sensing Workshop. I use the written form to archive part of the embodied practice that would be normally delivered as a participatory workshop.

between you and me (2023). is the last piece of work I co-made with Christine Cornwall with and for a trio of musicians from the Nadar ensemble. This piece was commissioned by the contemporary music ensemble Nadar and Gaudeamus Music Festival in Utrecht with a pre-scheduled plan of touring at three contemporary music festivals in Europe: Warsaw Autumn in Poland, Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival in the UK and Gaudeamus Festival in The Netherlands. The process contended with external restrictions, scale and co-creative challenges but also benefited from great technical resources and support as well as the opportunity to work with established contemporary musicians.

Embodied research into existing techniques and practices

In parallel with the creative work presented in this portfolio, I have sampled a range of performance practices that other people developed. These embodied approaches for working expressively with voice and body form the basis of training in many academic institutions and beyond. They are knowledges that tend to travel from body to body or to exist in books that capture them as methods that can support the doing but are incomplete without a teacher. Examples of such 'methods' books include Action Theatre by Ruth Zapora (1995), Impro by Keith Johnstone (Johnstone and Wardle, 1979), Games for actors and non-actors by Augusto Boal (2002), Exercises for Rebel Artists by Guillermo Gómez-Peña (2013), The invisible Actor by Yoshi Oida (2013), Freeing the natural voice by Kirstin Linklater (2006). As useful as these books have been as archival artefacts of practices or contextual grounding for this research, I have never learnt, and not for lack of trying, how to do practical things from them. Instead I immersed myself in workshops, residencies and private lessons with people that taught some of these and other performance practice approaches directly. The purpose of this was twofold: one the one hand, as a form of practice (as opposed to literature) review - familiarising myself with what is already out there in terms of embodied techniques in order to situate and inform the development of my own composition practice, and on the other hand, as embodied training and performance development for my own expression - benefiting directly from the knowledges these techniques were disseminating by accumulating know-how in my performative body. Later on in the research (particularly during the Splendor micro-residency) I borrowed some of the techniques that I resonated with, using certain exercises as entry points into group togetherness, testing and developing my own creative leadership style.

I detail below some of the training I undertook, referencing the closest book or website that affords a deeper dive into these practices and practitioners:

-

Online Vocal improvisation with Maggie Nicols, (Biography - Maggie Nicols, 2021)

-

Online and in person Roy Hart voice with Margaret Pikes (Pikes and Campbell, 2020)

-

Ruth Zaporah’s Action Theatre (1995) - taught online by Kate Hilder (Hilder, 2024) and in Montreal by Sarah Bild (La Poêle, n.d.),

-

Feldenkrais (The Feldenkrais Guild UK, 2024) - Kate Hilder,

-

Theatre and performance training influenced by Yoshi Oida, Jerzy Grotowski, dance, yoga, capoeira - taught by Persis-Jadé Maravala during DRIFT residency - artistic director of ZU-UK (Zu-UK, n.d.),

-

Skinner Releasing Technique (Skinner Releasing Institute, n.d.) with Susanna Hood (Montreal) + Kirsty Alexander (Glasgow),

-

Emotionally Integrated Voice with Fides Krucker (Krucker, 2022) (Toronto)

-

Viewpoints (Overlie, 2016) with Gabriela Petrov (Montreal),

-

Fitzmaurice Voicework (The Fitzmaurice Voice Institute, n. d.)- introduced by Noah Drew in Montreal; trained formally as a teacher in myself in NY and LA.

I extract here a few specifics from these practices that have had an impact on the development of my work.

Online Vocal improvisation with Maggie Nicols

‘While vocalising a singular pitch in a myriad of ways, improvise on the piano playing other pitches meant to sit in sonic difference alongside the sung note.’

I’m paraphrasing above one of the exercises Maggie Nicols offered in one of our online sessions that took place during the Covid pandemic when face to face interactions were restricted. The exercise helped me develop expressive diversity by pushing me to discover what is available in only one pitch. While that was undoubtably useful, the effort of holding onto my own pitch, resisting being pulled into another sound was even richer. This tethered me to a precise sonic sensation that helped me accumulate felt experience of how it is to sonically be prioritising myself over another - in this case represented by the sound of the piano. I took this exercise further by repeating it every day for a week while streaming myself live on Facebook. To live stream online to a controlled audience was my way of building resilience with exposure during a time when online audiences were the only option.

This exercise was one of the first practical examples I tried out that worked as inspiration for further investigations into sound as a tool for self-sensing.

———————

Ruth Zaporah’s Action Theatre

Action Theatre was the first improvisation training I did in which I was supported to express sensations through voice and body through playful exercises in pairs or group settings. Movement and physical awareness are integrated in this practice to work alongside voice.

The classes had a well-defined progression over the eight-week online course I did with Kate Hilder, moving from expressing physical sensations alone to expressing in non-verbal interactions in pairs (e.g. one person moving, the other sounding the movement with voice), towards expressing in groups with words that played with sonic content as much as with meaning, while our bodies moved through space. Action theatre helped me connect with physical impulse under clear frameworks supporting a gentle opening towards the other. The prioritisation of sensation over meaning was particularly useful, even if the separation into distinct sensory channels was eventually limiting.

I adapt and incorporate some of the Action Theatre exercises in the work I did on the Splendor micro-residency.

——

Roy Hart voice with Margaret Pikes

The Roy Hart approach is an established approach to vocal training coming from a theatre lineage. Voice is connected and tethered to the body, exploring the potential effects different body parts have on vocal quality, using a lot of play and imitation of characters (such as the big giant living in the belly) to extend the expressive range. The in-person Roy Hart group workshops I took with Margaret Pikes offered playful approaches to group sounding that bypassed analysis in order to get closer to group expression. They resemble Action Theatre exercises but focus in much more on vocal expression.

An example of such an approach is the group imitation exercise. In this exercise, one person moves and sounds in front of a group of improvisers for approximately five seconds with the group then imitating their sound-body movement precisely. This happens a number of times, the group then moving from precise imitation to a conversational response that retains the affective quality the single person has fed into the interaction but responding not as individuals but as a single unit. A practical adaptation of this exercise is to be found in the Splendor micro-residency documentation of practice.

This kind of exercise relies on explicit relational dynamics that enable expression to be seen, heard and played with outside of regular social norms. This intentional and explicit reorganisation of socialities has resonated deeply with my ADHD selfhood, offering a space for impulses often silenced to manifest freely in the company of others.

Roy Hart work has helped me expand my expression the most through the playful and relational approaches to group expression which connected multiple vulnerable bodies in silly interactions such as pretending to be stupid giants or butterflies in flight.

———

Zu-UK DRIFT Residency

I experienced Persis-Jadé Maravala's work on the weeklong DRIFT residency she runs yearly. It is difficult to be concise about what Jadé teaches as her approach is informed by many different techniques accumulated through performing and training over many years. For me, the residency Jadé led was the most intense performance training bootcamp I ever did. Each day would start with a group silent cleaning of the floor of the studio followed by 10 minutes of silent group eye contact. The daily exercises would range from blindfolded guided walks to capoeira group dancing in which we were encouraged to steal a dancing partner, taking up space. More than individual techniques, what I learnt from Jadé was what good leadership looks like. After the residency I wrote this:

The DRIFT is very much Jadé’s world. She defines it and keeps shaping it as it goes along. Her strength and way to hold a room are admirable. Her belief in pushing boundaries is intoxicating. You have no choice but to push yourself and understand your own boundaries. This is not a residency for people that feel powerless. You have to be able to hold your own and draw your own lines. You will be pushed and through that push you will grow. But growing isn’t easy, as roots grow deeper or stems reach towards the sky the whole organism vibrates and redefines itself. The DRIFT is a space of intensity. Of intense connection with others, of intense confrontation with oneself. The atunement to others through physical exercises left me feeling something close to magic. If magic would be real life as it’s supposed to be. It made me aware how much individuality and inwardness have been normalised in my life. That over the years I’ve grown layers of protection against others that keep me from seeing them or being seen. This work is for the shedding of the armour. For the peeling of the onion layers so that you can lay bare in front of someone as they lay bare before you and see each other. Really see each other and be seen. I will miss that safe but exposing place that Jadé created with so much poise. By the end of it, despite us having very different artistic goals and practices, our group had our hearts tethered to each other. We cared for each other. We rooted for each other to succeed, to achieve our goals, to progress in our journeys. When things got too much we were there for each other. We cried and laughed and loved and sometimes hated each other. All of this over 5 days. I am bewildered at how someone can facilitate a place that holds such intense emotion and authenticity in such a short amount of time. As Jadé said, this is her life’s work. And it’s left me feeling a renewed sense of possibility and trust in my own intensity and the intensity of others. (26 March 2022, London)

——

Fitzmaurice Voicework

Fitzmaurice Voicework (FV) is an approach I came to quite late in my research (year four) while I was on a Visiting Doctoral Researcher trip in Canada. I worked with Noah Drew, my academic supervisor at Concordia University, for six months, slowly familiarising myself with this work.

In short, FV is a very physical approach to voice that uses an involuntary muscle vibration in the legs or arms, a tremor or dynamic effort, to affect breath. This tremor can pass through the body if the body is released, clearly indicating the zones of tension and putting one in contact with them. Over time, the physical effort of the tremor familiarises the body with how to use minimum effort when supporting breath. Facilitating this work requires skills to support students through potentially intense level of contact with one's emotions that can get activated when releasing previously held tensions. For this reason FV has a trauma-informed approach and is taught with a deep somatic awareness and care for the student.

During my sessions with Noah, I was given a high degree of autonomy to feel whatever I was feeling and to integrate that into what and how we did things. This ability for my biorhythm to inform the speed and content of the work, not differentiating between emotion or sensation but taking it all as feeling that can move through breath was an important insight.

Fitzmaurice work had such a deep resonance with me, both as a practice and as a pedagogical approach that I pursued a teacher certification in the method. After two years of training, in the summer of 2025, I became a fully certified Fitzmaurice Voicework teacher. The ways this approach can influence pedagogy or sensory sonic making beyond the tentative ways explored in this research are avenues for further exploration.

Skin made of bone.

Skin made of rough rough diamond and stone.

Skin so transparent everything is on show.

Skin so fluid, it struggles to form.

De-form, re-form.

Protected.

Over-protected.

Climbing over itself, safer and safer.

Sedimented. Amalgamated. Diffuse.

Other bodies are a threat.

They might glimpse, might touch, might guess

Her.

Other bodies have been unkind,

overpowered

Her.

Relocating.

Repeating mumbled mantras of care

Babbles, softly uttered

Over and over and over again.